Declaring war on the planet

When humans wage war on each other, we're not the only ones paying the price

Since the dawn of the Atomic Age, there has been speculation about what the world would look like if nuclear warfare were to kick-off in earnest. Not only do weapons of mass destruction vaporize everything in their blast radius, human and non-human alike, they disperse radioactive material for months across hundreds of kilometers.

Anything that comes in contact with the fallout from the atomic cloud becomes contaminated: water, soil, crops, animals, rain. Radiation could linger for years, but the bomb pulse, an increase in global carbon-14 resulting from their detonation, could affect human health 8,000 years down the line.

If multiple weapons are employed in a short period of time, the resulting soot could block enough sunlight to lead to significantly cooler temperatures, a.k.a. a nuclear winter. Without sunlight, plants would fail to grow, and with animals ill and contaminated with radiation, famine would be inevitable. Only those with the foresight to store enough water and food would survive.

These extreme effects wouldn’t be contained to the country or continent on which the A-bombs were dropped. They would be felt globally. This is one reason why countries with nuclear arsenals have wielded them only as a deterrent since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that marked the end of World War II.

Despite the Treaty of Non-Proliferation of the 60s, which includes disarmament and the elimination of nuclear arsenals in its goals, South Africa is the only country that has voluntarily destroyed their stocks and halted production. Regardless, TV shows like Silo and Fallout in which the privileged few are only able to survive in well-stocked bunkers keep the concept of a post-apocalyptic nuclear landscape fresh in the collective consciousness.

While the environmental destruction resulting from nuclear warfare could be considered common knowledge, there seems to be little to no understanding of the effects of non-nuclear warfare outside of population and infrastructure decimation when, in fact, it can also result in long-term devastation of local ecosystems and impede any viable post-war recovery.

The data being published about the environmental effects of Israel’s genocidal campaign in Gaza are staggering. I’ll clarify that focusing on environmental damage done in the last two years is not meant in any way to diminish or overshadow the extent of human death and suffering that has been inflicted on the Palestinian population. In order not to glaze over these atrocities, I’ll share some key facts.

An inquiry by the UN Human Rights Counsel has found that the Israeli military imposed a total siege, including blocking humanitarian aid, leading to starvation, systematically destroyed healthcare and education systems, committed systematic acts of sexual and gender based violence, directly targeted children, and carried out systematic and widespread attacks on religious and cultural sites.

All this in addition to the killing of over 68,000 people, 20,000 of which were children, 1,700 of which were medical professionals, and over 250 of which were journalists. The Israeli Defense Force’s actions don’t only constitute war crimes against the Palestinians, but also against the environment, some argue. After all, the small Mediterranean state is a “biodiversity hotspot where wildlife from Europe, the Middle East, and Africa meet,” writes Fred Pearce for Yale Environment 360.

Between the bombing campaigns, aircraft reconnaissance, tanks and other military vehicles, Israel is estimated to have emitted at least 15 million tons of carbon dioxide in the last two years. Now, the process of clearing debris and rebuilding Gaza could double the genocide’s carbon footprint. In total, the emissions will be higher than those of many countries, including Costa Rica, Afghanistan and Zimbabwe.

Before the war, Gaza had one of the highest density of rooftop solar panels in the world. That, and much of its other infrastructure, was decimated. As the supply of fuel and electricity dwindled, waste water treatment plants faltered and raw effluent polluted not just the Mediterranean, but underground water reserves, too. Without energy, the desalination plants that supplied much of Gaza with water came to a still, which left many Palestinians no choice but to rely on these contaminated wells.

Of course, other crucial services like waste collection also stalled, forcing residents to resort to the creation of makeshift dumps and open-air waste burning. When you addition the fact that 40 million tons of rubble containing human remains, asbestos, and unexploded ordnance litter the street, the colossal task of clearing it away and rebuilding comes into focus.

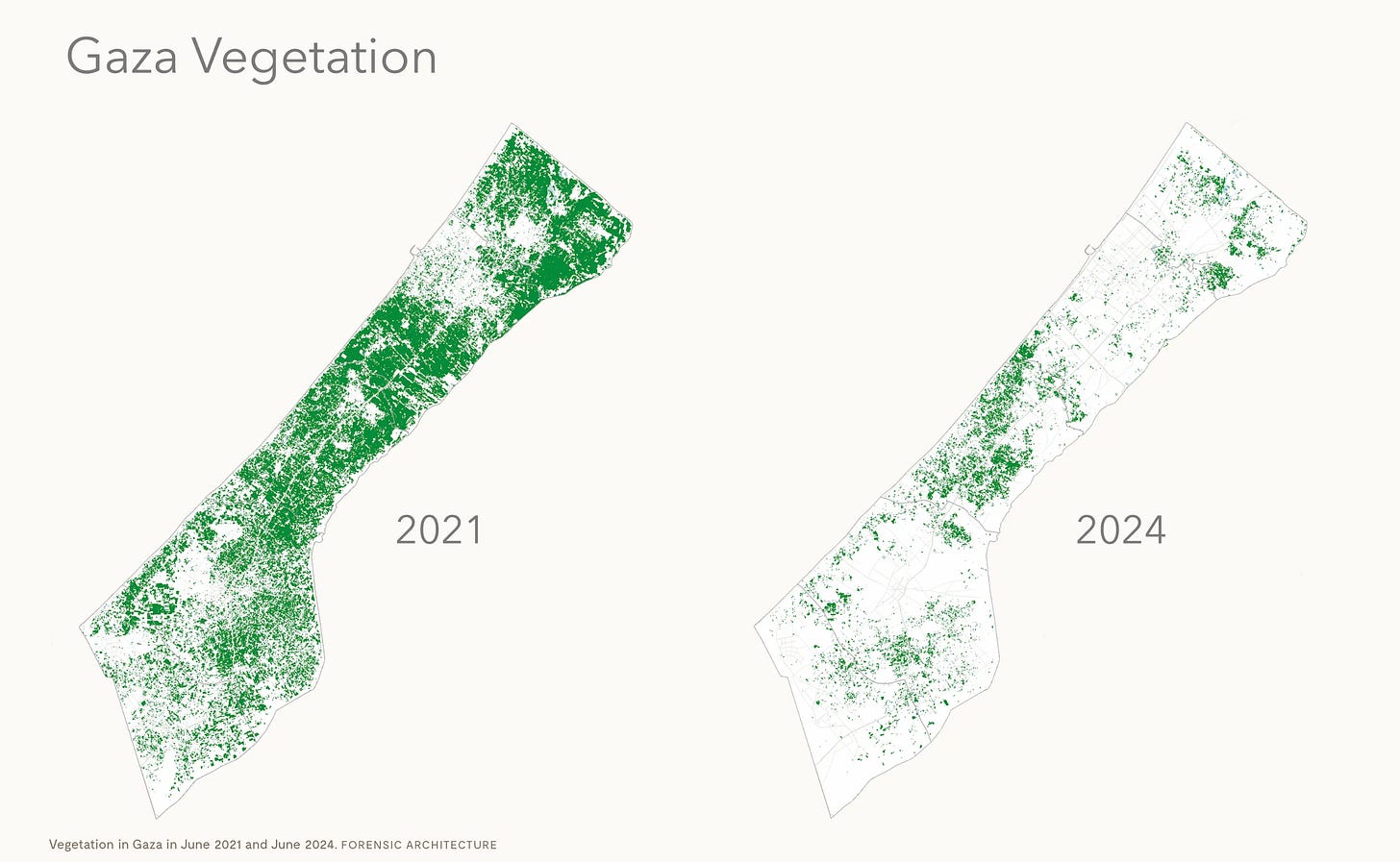

Two-thirds of Gaza’s farmland was damaged, and 80% of its trees were stripped away. This once fertile land is now at risk of permanent desertification. This would mean that even if given the necessary resources to rebuild infrastructure, Palestinians would be left with little arable land to grow food on, threatening their ability to be self-sufficient.

This impacts wildlife as much as it impacts humans. Animals that relied on the water from the Wadi Gaza now find it polluted, much like those native to the Mediterranean coast. Important wetlands called Al-Mawasi were also victims of bombing campaigns. It will take years of consistent ecosystem recovery efforts to reverse the damage done.

The most urgent need is for humanitarian aid, emergency shelter, hygiene and sanitation services. Then, critical utilities need to be brought back online; think solar panels and water treatment plans. Only then will there be time and resources to spare for non-human species and the ecosystems they rely on. This isn't criticism but a fact.

It’s only natural that we take care of the survivors from our own species before sparing a hand for others. Granted, this view fails to recognize that humans are still part of a broader ecosystem and will suffer as much as any other creature when the balance is thrown off. Not only that, but nature knows no borders. The environmental damage done just kilometers away in Gaza will have an effect on Israel, too.

They’ve already experienced this when the waste water treatment plants failed and sewage spewed into the Mediterranean. Israelis couldn’t wade past their shore without encountering water polluted with Palestinian waste. When your neighbor’s that close, if their house burns down, you can expect your lungs to blacken with smoke at the very least.

Just like how small island nations responsible for less than 1% of global emissions are facing the worst consequences of a climate crisis driven by countries in the Global North, the effects of the catastrophe we’re facing are already erratic and unpredictable. As the urgency to cut global emissions rises, there’s nothing more counterproductive than war.

This doesn’t apply only to the conflict in Palestine. Ukraine is experiencing something similar under Russia’s tireless onslaught. Hundreds of thousands of lives have been lost in the last four years, water security has been put at risk, and many habitats have been endangered. Ukraine, too, has targeted Russia’s oil refineries, undoubtedly releasing tons and tons of greenhouse-gases upon their destruction.

Just like in Gaza, trees are disappearing, soil is becoming contaminated, and future economic and ecological recovery is being put in question. Just like in Gaza, environmental issues are the least of Ukrainian’s worries and the last of their priorities. “We want the war to end,” some were quoted as saying. “We’ll endure whatever the state of our environment is, as long as things get better.”

That leaves only one viable option to protect our planet from the devastation of war: peace. Obviously, it’s not as simple as it sounds. In order to achieve peace, many complex, underlying dynamics must be tackled. Factors that contribute to social instability like economic inequality, high unemployment rates, political corruption, and the social marginalization of certain groups can all lead to conflict.

Therein lies the importance of sustainable development that encompasses all three pillars of sustainability: economic, environmental, and social. Without a three-pronged approach, groups are bound to get stuck in a vicious cycle in which economic vulnerability and political instability lead to violent conflict, which then exacerbates poverty indices and destabilizes the dynamic further.

In war-torn areas like Palestine, Ukraine, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, the difficulty lies in breaking this cycle. After years of oppression, it’s unreasonable to expect the victims to forgive and forget. It’s even harder to convince those that have grabbed power by inhumane means to give it up.

While I may not have an answer for how to achieve peace in the Middle East, I can say with certainty that any temporary truce must be taken as an opportunity to implement sustainable development initiatives if we hope to generate lasting change. If not, we might just end up counteracting global warming with the anti-greenhouse effects of a nuclear winter.