More money, more problems

Growth has long been considered a stabilizing force in our society, but does that still hold true today?

Ancient Greek philosophers like Aristotle, Socrates, and Plato would have found the idea of working beyond what was necessary abhorrent. In the Middle Ages, religious thinkers claimed that it was in leisure, through contemplation, that one grew closer to God.

What these great minds were suggesting wasn’t that we should all have unlimited time to “bed rot” and “doom scroll” and no obligations. They were pointing out the necessity of having free, unstructured time to cultivate a rich inner world.

Today, this type of productive leisure has become unreachable for the great majority of the world population. Even with global unemployment at a historic low, billions are finding that their jobs aren’t delivering on the financial security that they once promised.

Yet, the answer that is repeated by world leaders everywhere is the same: with sufficient economic growth, there will eventually be enough to go around. People just need to work a little harder for a little longer, and they will reap the benefits of progress and innovation. But is this true? And if it’s not, why has growth become such a widely accepted answer that it even crosses ideological divides?

The origins of our growth fetish

To understand how we even got to this point, we must go back to the era of the Enlightenment, when the perfect conditions arose for what later would become the capitalism we know today. At the time, early venture capitalists were financing excursions to the Americas with the sole purpose of exploiting their natural resources and accumulating wealth.

The colonial enterprise was built on a system of land seizures around the world, effectively privatizing the common resources that were previously used for subsistence farming by many. This created a system of scarcity, where those deprived of their land were forced to become wage laborers at best or slaves at worst. States played a key role by guaranteeing these new property rights and promoting racist ideas that dehumanized those victimized in the process.

A large part of this dehumanization was the diffusion of the myth of linear progress. Most cultures until then regarded time as cyclical, but the spread of Christian apocalypticism and mechanical clocks reframed it as a linear and objective measure. In this linear understanding, people could be divided into the primitive and civilized based on arbitrary and racist standards, thus justifying the colonial endeavor as a way of developing colonies into engines of productive output.

In the world the colonizers had created, everything from people to land had become comparable and interchangeable, things that could be traded as merchandise through property rights. Not only natural resources, but the work of women and the colonized also existed only to serve mankind (white males) and could be possessed, exploited, and changed at will.

Somehow, amidst this whole process, home keeping became devalued and excluded from measures of economic output. Only male-dominated sectors would be factored in when, in the nineteenth century, the concept of the economy was formalized as a separate entity from daily life.

It was under these productivist growth societies that many civil and labor rights wins came to be. Increasing production created surpluses that enabled the subsequent distribution of wealth through social security systems and public infrastructure. The power of the strike, as well, came from the ability of workers to freeze the means of production and sabotage the system of growth.

Growth became a stabilizing force in an ever changing society. History proved that, as economic output increased in a country, social improvements followed. However, what some failed to see was that those gains were made by those who opposed unrestrained capitalist systems, not as a natural result of the systems themselves. In fact, looking back, we can see that even the stabilizing effect of this growth benefitted only those at the core of the system.

You see, growth necessarily requires the input of cheap labor and resources, while countries in the global South bear the brunt of the cost. For the last half century, growth has been showing diminishing returns and doing nothing to reduce inequalities even within countries in Europe and North America. Instead, we are seeing the devastation and havoc these systems are wreaking on ecosystems and communities.

Measuring well-being

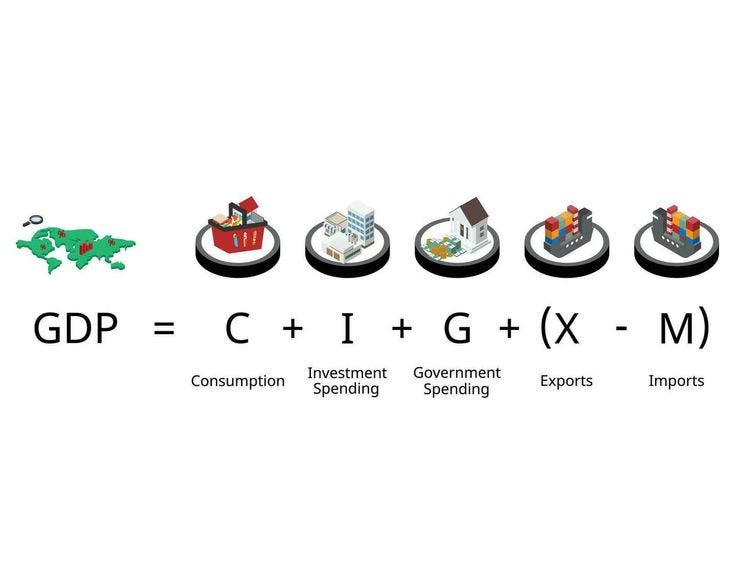

Our obsession with growth culminated in the creation of the GDP in the 1940s. After the Second World War, the United States was keen to prove the superiority of capitalist systems over socialist ones. To do so, they created the Gross National Product to prove the success of capitalist accumulation and prove the socialists failures due to their failure to grow.

What we are finding today, however, is that GDP growth does not equate to better quality of life for a country’s citizens. Yet, development initiatives in low-income countries still rely on colonial logic that states that increased economic output will naturally lead to the solution of social ills.

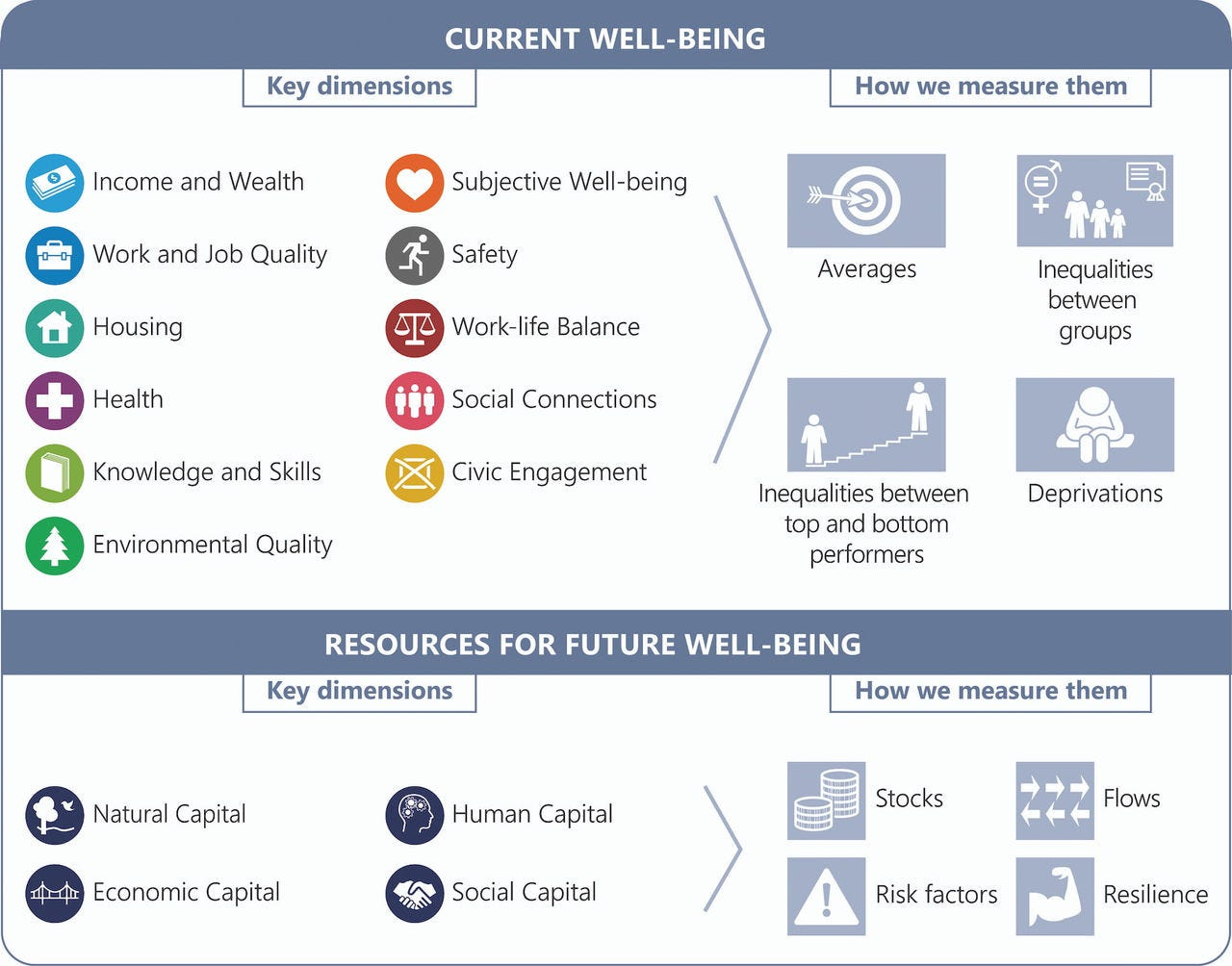

Arguments for replacing GDP with measurements that actually focus on people’s and the planet’s wellbeing are becoming increasingly commonplace in spaces where environmentalists gather. Income and wealth still factor into these calculations, but so do things like access to housing and healthcare.

Meanwhile, policymakers are grappling with the challenge of ensuring financial well-being when jobs prove too low-paying or precarious to provide their citizens with stability, much less prosperity. All the while, inflation erodes buying power and jeopardizes families’ resilience.

Some countries are turning to unemployment insurance schemes, others are providing stipends to families with children. What’s readily apparent is that we can no longer assume that economic productivity on an individual scale, i.e. having a job, or on a national scale, i.e. GDP growth, equals well-being.

The worst part is that even those at the core of the system who are reaping the benefits are not well. Radicalization is on the rise in wealthier countries as what used to be fringe beliefs grow into mass movements. In “The West is Bored to Death”, Stuart Whatley makes a poignant observation.

Merely being a registered Republican or Democrat doesn’t lead one to join a violent insurrection or transform one into an activist for unpopular causes. What extremist groups have in common today is their recruitment methods. Those who fall into their clutches tend to spend all their free time and attention online.

This brings us back to the first paragraph of this article. People are failing to find productive uses for their leisure time for many reasons, not the least of which is the competition companies are in to colonize our attention span (see the attention economy). Without healthy uses of their free time, individuals are wont to find themselves empty inside and feeling purposeless.

This is exactly what mass movements feed on. People who are unhappy with their own lives and find meaning through something larger than themselves. Instead of investing their time into cultivating friendships, contemplating the big questions of life, and public service, adherents to these movements content themselves with a voyeuristic appropriation of the movement’s successes as their own. They would rather project themselves onto something abstract than face their own loneliness and boredom and take steps to alleviate them.

Whatley says that “American greatness has produced a society whose members know not what to do with the freedom and abundance that earlier generations secured.” We could just as easily replace “American greatness” with “our pursuit of infinite growth”.

TL;DR

The growth paradigm may have arisen from a legacy of colonization, but it played an important part in stabilizing societies for many decades. Because of that, it became common sense to policymakers and executives that growth was always the right answer. Lately, however, that logic has begun to erode. Growth has been yielding decreasing returns and is losing its stabilizing effect both in the center of the system as well as in the fringes.

At the core of the system, those who benefit the most from economic growth have become unhappy and are turning to mass movements to find purpose. This can be attributed, in part, to the growth paradigm that tells them that their purpose should be output and production. Then, they are disadvantaged once more when their leisure time is overtaken by corporations pushing addictive, vacuous content on them in search of their own corporate growth.

Those who suffer the most from this dynamic, however, are clearly those at the fringes of the system. Those who were promised that with enough growth, they could also reap the rewards they saw those at the center of the system enjoy. In reality, they were relegated to the role of provider of cheap labor and resources to keep the machine going. All the while, the system perpetuated an ecocide in the countries of the Global South.

At this point, we must ask ourselves who this system is serving. And if it doesn’t serve the majority, then we must dispense with it and find another way to stabilize our societies. This is the time to imagine what a different system could look like. Let’s not box our imagination in with “this is the way it’s always been”. After all, I hope that if this article has conveyed any message, it’s that that’s simply not true.

It would be nice if our leaders considered the well being of their constituents instead of their own economic interests. Great article!