When you know the price of everything and the value of nothing

Our economy is propped up by natural capital and "free" ecosystem services. Who's left holding the bill?

Loro Piana is a hundred-year-old Italian brand known for its high quality cashmeres. It’s part of the LVMH portfolio and meant to represent the apex of luxury. One Loro Piana sweater can cost up to $11,000 USD. In the U.S, someone making minimum wage and working 40 hours a week earns $15,078 per year.

“Luxury products are sustainable by nature,” says the chairman of Loro Piana, Antoine Arnault. “That’s what makes them so special. They are made from the highest quality materials; they are durable; they are repairable. That is what separates us from the rest of the fashion industry.”

If you’re aware of the recent scandals surrounding this brand, this statement will probably cause you to scoff or shake your head. If you’re not, let me lay out the evidence submitted to the Milan Tribunal that found Loro Piana guilty of labor violations.

The court’s findings show that the brand subcontracted the production of its garments through front companies to Chinese-owned factories in Lombardy, which further outsourced work to unregistered workshops, violating laws on traceability, minimum wage and worker safety.

Upon inspection, the authorities discovered that employees were “forced to work as much as 90 hours a week, all 7 days, the laborers were only paid €4 an hour, and housed in illegal dwellings inside the factory”. According to separate investigations from Reuters, one worker said he was hospitalized for over a month after being beaten for asking for unpaid wages.

Mind you, similar issues were found in the supply chains of brands like Dior, Armani, and Valentino. The authorities didn’t just prosecute these companies for exploiting illegal immigrants, but for making misleading claims about the environmental and social standards of their production processes, a.k.a greenwashing.

You know what’s even worse? Loro Piana’s signature vicuña wool, the same one used to make items worth thousands of dollars, was being sheared by members of the Lucanas indigenous group of Peru who work for free during annual shearing periods. Most of these volunteers live in houses made of mud without indoor plumbing despite having been Loro Piana’s provider for decades. The kilo of wool they sell to make an $11,000 sweater is sold for less than $300.

Let’s be generous and say that one sweater takes one week to make and a kilo of wool. That would put labor costs at €4 x 90 hours a week = €360 or $417 USD. Add in the $300 and the brand still gets to pocket over $10,000 per sweater. That’s a profit margin of over 93%. A little over 3% goes to the sweatshop workers, and just 2% of the profit is shared with the Lucanas. The brand could literally increase their labor and raw materials costs by ten times and still make a 50% profit on every item sold. They choose not to because they’re not trying to create shared value for their suppliers.

These so-called sustainable by nature luxury brands are engaging in the same race to the bottom as every fast fashion producer like Shein and Zara. The Milan Tribune’s investigation has revealed that they even use the same tactics: sub-contracting work over and over until their supply chains are complex enough that they can claim plausible deniability. Even when they have the resources and power to improve the communities they rely on, they choose to be exploitative and extractive instead. Still, these brands thrive.

Even as Chanel’s iconic flap bags become notorious for quality issues like peeling leather and tarnished hardware, they’ve doubled the price from $5,000 to $10,000. “Once-revered establishments that prided themselves on craftsmanship, service and cultivating a discerning and loyal customer base have become mass-marketing machines that are about as elegant and exclusive as the Times Square M&M’s store,” writes Katharine Zarrella for the New York Times.

Does a higher price always equal more value?

Believe it or not, this article isn’t actually about sustainable fashion. It’s not about labor rights or human rights either, despite the lengthy intro. It’s about how we value things. We’ve been trained under capitalism to equate price tags with value, but as these examples have demonstrated, it’s increasingly a false equivalence.

Brands have learned to manufacture scarcity to pump up their prices. Entrepreneurs have been taught to create new problems just to sell consumers a solution. The global economy relies on abstract, immaterial activities like stock trading to prop up imaginary capital markets. It’s what we call the financial economy versus the real economy, which in short, refers to the production and sale of physical goods and services.

Transactions in the real economy are the backbone and lifeblood of communities. Take your locally-owned bookstore or coffee shop. Every dollar spent there goes into the pockets of its employees and owner, who then spend that money in their neighborhood. However, once the coffee shop is bought up by a private equity firm, suddenly part of its value shifts from the real economy to the financial economy. Now, the profit is being siphoned out of the community and into the PE firm’s pockets.

It’s easy to understand how the financial economy is rooted in the real economy. If there’s no production and sale of goods, there’s no basis on which to construct imaginary capital tools like stocks, bonds, etc. This is one of the reasons why financial experts see things like Bitcoin, which are not grounded in any aspect of the real economy, and disagree with their being used as currency. There is no material asset underlying them to provide stability and security.

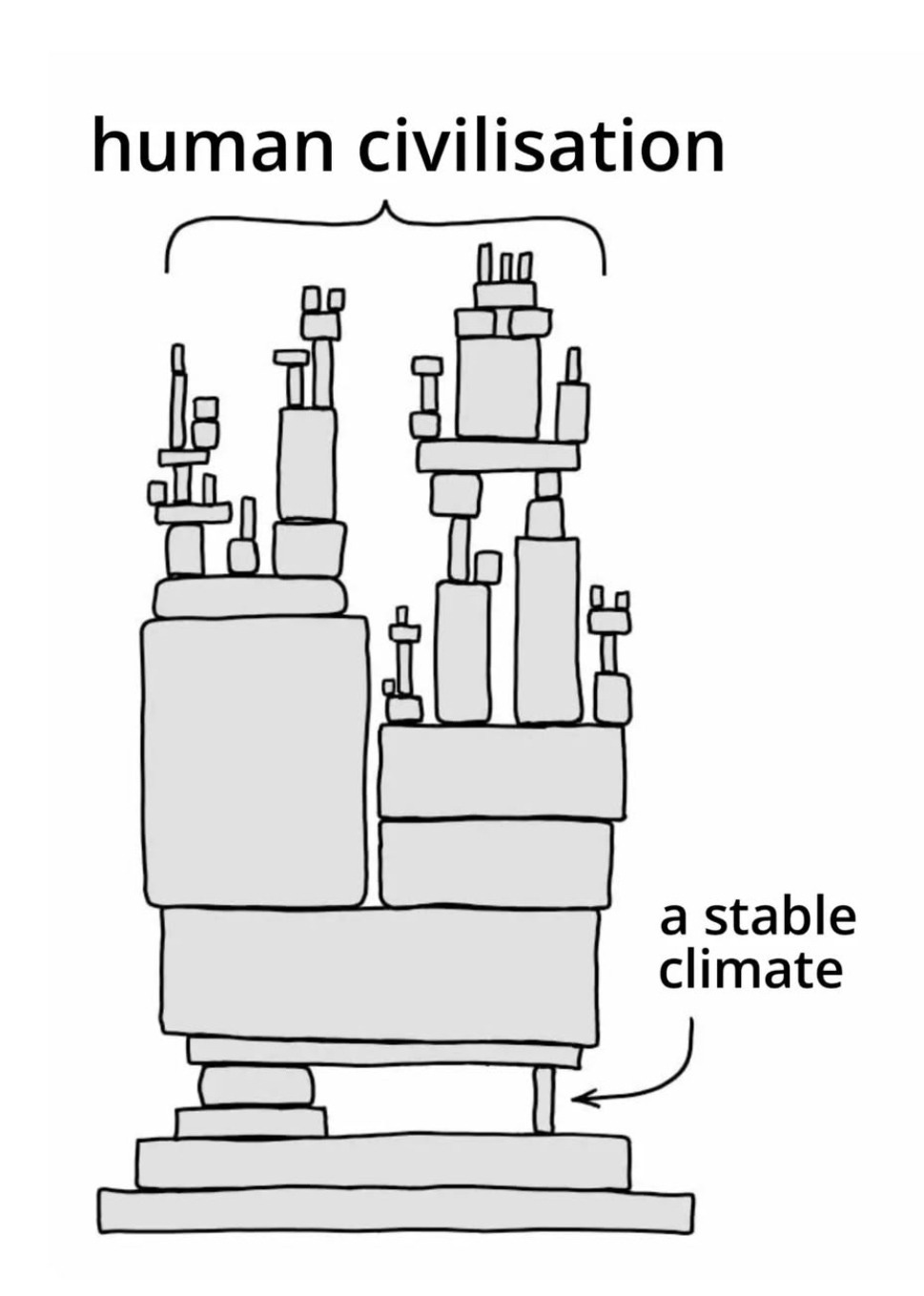

So, if the financial economy is propped up by the real economy, what is the real economy propped up by? The answer is simple: our planet’s abundant natural resources. Farmers would go bankrupt without access to water reservoirs and underground aquifers. In California, both are becoming exhausted. A stable climate and predictable weather patterns affect not only agriculture, but logistics. With the rise in extreme weather events, ports and global trade networks experience increasing disruptions.

There’s a reason that financial institutions like stock exchanges can’t afford to turn up their nose at sustainability topics despite the growing anti-ESG rhetoric in the U.S. If investors want to make informed decisions on their portfolios, they must be aware of climate-related risks.

Our entire economic system depends on having a livable atmosphere, so why isn’t every Fortune 500 company investing in sustainability solutions like their future depends on it? The answer is complex and requires an explanation of several innate human biases. Perhaps I’ll get into those in another article. Today, I want to focus on one very interesting argument, that of natural capital and the ecosystem services it provides.

How do we value things without a price tag?

Some economists argue that, while our economy is reliant on healthy ecosystems to function, the value of these naturally occurring services is not represented anywhere in monetary value. Simply put, because these ecosystem services don’t have a price tag attached, they are severely undervalued and under-protected, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation and depletion.

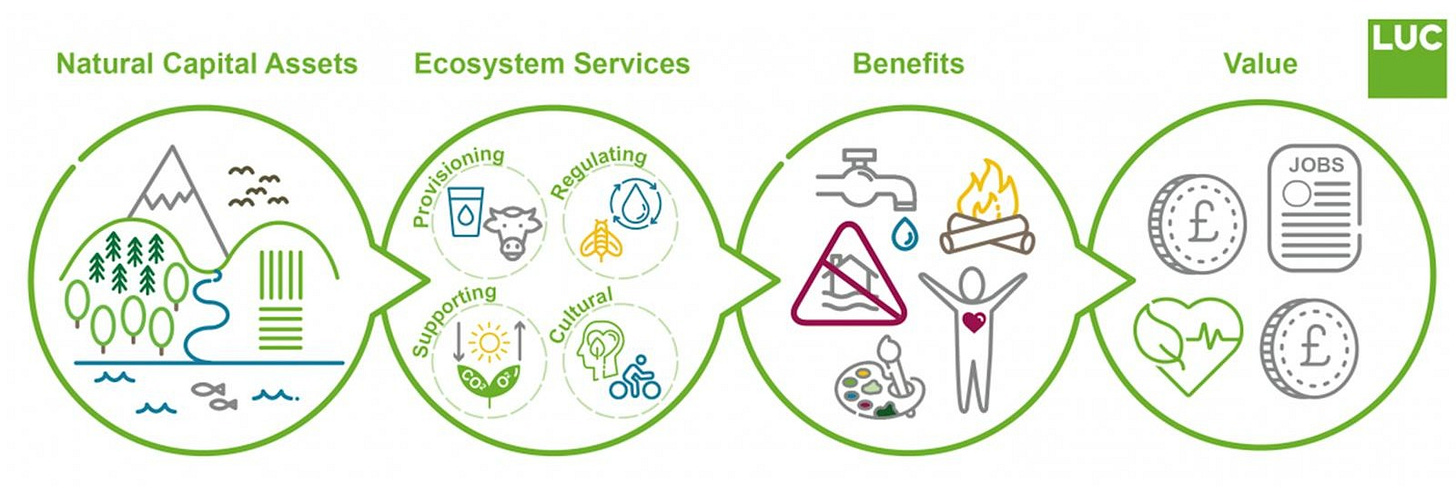

Let’s take a step back and define these terms before we go any further. Natural capital refers to the assets of the living world: plants, rivers, soil, animals. The benefits that we gain from these assets are ecosystem services. A forest is a natural capital asset. The ecosystem services it provides may include a timber supply, reducing water run-off, and providing a peaceful backdrop for leisure activities.

With just that example it’s easy to see that ecosystem services can range widely and fall into different categories. They can provision products like food. They can regulate natural processes to reduce flooding or improve air quality. They provide support services to help other ecosystem services function. And they offer non-material cultural benefits essential to our health and wellbeing.

In the EU, a network of protected sites called Natura 2000 cover over 18% of the union’s land area and thousands of marine sites. A report attempting to put a value to the ecosystem services provided by these sites estimated a total of 200-300 billion euros in benefits. The broad range is a reflection of how difficult it is to quantify these assets since calculations rely on estimations and assumptions.

The European Parliament is fully aware of the methodology’s shortcomings, but remains intent on using these figures to promote biodiversity preservation. Not only do these calculations illustrate the economic benefits of investing in environmental initiatives, they can be used to evaluate the financial costs and benefits of different policies. Most importantly, they can be used to establish market-based mechanisms to promote preservation.

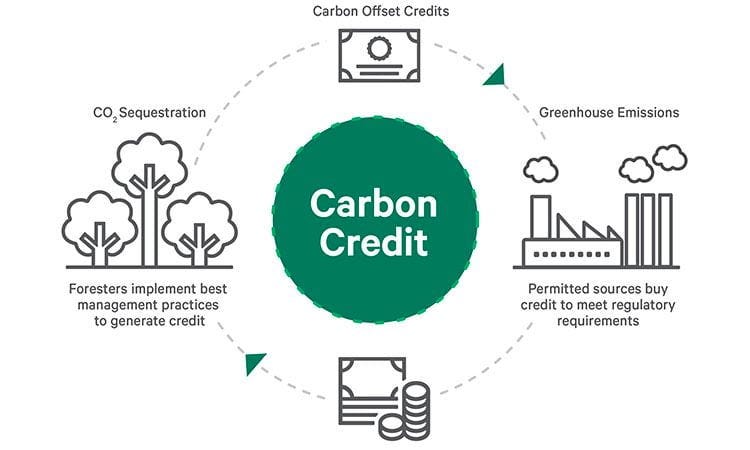

It’s the same logic behind the creation of voluntary carbon markets in which companies and, increasingly, individuals buy into reforestation or similar projects in exchange for carbon credits. In a perfect world, we may be able to convince our government and corporate leaders to safeguard the living world purely because it’s the right thing to do. In reality, demonstrating economic benefits is much more effective. It’s a clever workaround in a system that has conditioned us to respond only to monetary incentives.

Costa Rica’s government won the 2020 Global Climate Action Award for successfully implementing a system of Payments for Environmental Services following these principles. To date, it has rewarded hundreds of thousands of Costa Ricans for contributing to the reforestation of their country and the preservation of its biodiversity.

This goes to show that people will act in more sustainable ways if the right incentives are in place. The main issue is that our current system doesn’t reward environmentalism. It values all the wrong things over what’s most important for our continued survival. Our entire civilization is reliant on natural capital and the services they provide for us. Yet, we’ve failed to manage them sustainably because their value isn’t being represented on a price tag.

It’s a problem sometimes referred to as the tragedy of the commons. After all, another word for natural capital can easily be common goods. They’re goods that you can’t prevent people from accessing just because they haven’t paid for them. Think about the mountains, the rivers. It’s because these natural assets are common goods that it becomes preposterous when a water bottling company puts river water in a plastic container and sells it back to us.

The tragedy of the commons occurs when the demand for these resources outpaces supply. Since there’s no barrier to accessing them, they are exhausted. In order to prevent this, individuals or communities must agree to limit their exploitation of these resources to a sustainable level, i.e. only take what can be replenished in a certain period. Those who fail to adhere to these new standards and persist in their over-exploitation are referred to as free riders.

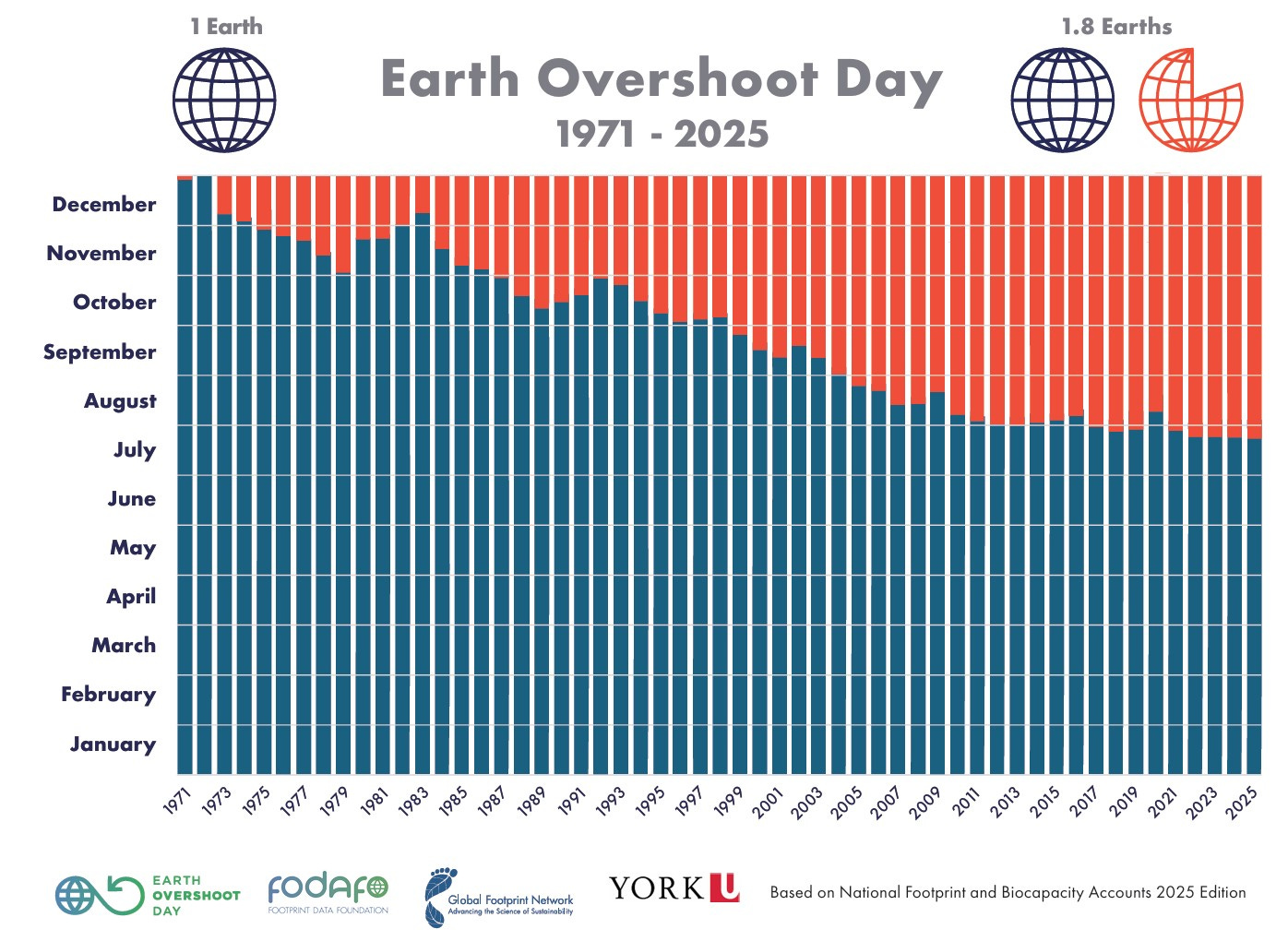

Therein lie the causes of our current over-exploitation of the living world. In many respects, we’ve failed to collectively agree to the limits of extraction. On July 24th of this year, we officially passed Earth Overshoot Day. In short, it means that by July 24th, Earth’s population had consumed the amount of resources our planet could replenish in one year. That’s why it’s also called the Ecological Debt Day. After this date, we’re using borrowed resources from the future.

The second cause is the abundance of free riders in our society and the economic system that encourages and rewards their overconsumption. As I noted earlier, this article is about value and our failure to recognize it. Somewhere between luxury brands and meme coins, we’ve lost the plot. It’s time to acknowledge the real cost of our current lifestyles and not just their price.