This is the new (hyper) normal

Our leaders' insistence that everything is well even as we see our system crumble has created a false reality we must come to terms with if we hope to affect any real change

I don’t remember what made me stumble across the BBC’s nearly three hour HyperNormalisation documentary, but I’m now recommending it to anyone who could have the slightest interest in it: my fellow sustainability professionals frustrated with our leaders’ seemingly willful ignorance, my friends with a conspiratorial bent that theorize about big government coverups, anyone who wonders how the Middle East became (or came to be portrayed as) a conflict-ridden zone…

“Over the past 40 years, politicians, financiers, and technological utopians, rather than face up to the real complexities of the world, retreated and constructed a simpler version of the world to hold on to power. As this fake world grew, all of us went along with it because the simplicity was reassuring.”

This is how the documentary begins. I will be loosely quoting it throughout this whole article to explain how we ended up here and how it’s sabotaged most attempts at real change, including climate activism. Understanding how our system is engineered to make social movements fail is critical if we’re to circumvent these pitfalls. That way, we can dedicate our time and effort to the actions that will lead to systemic change and real impact.

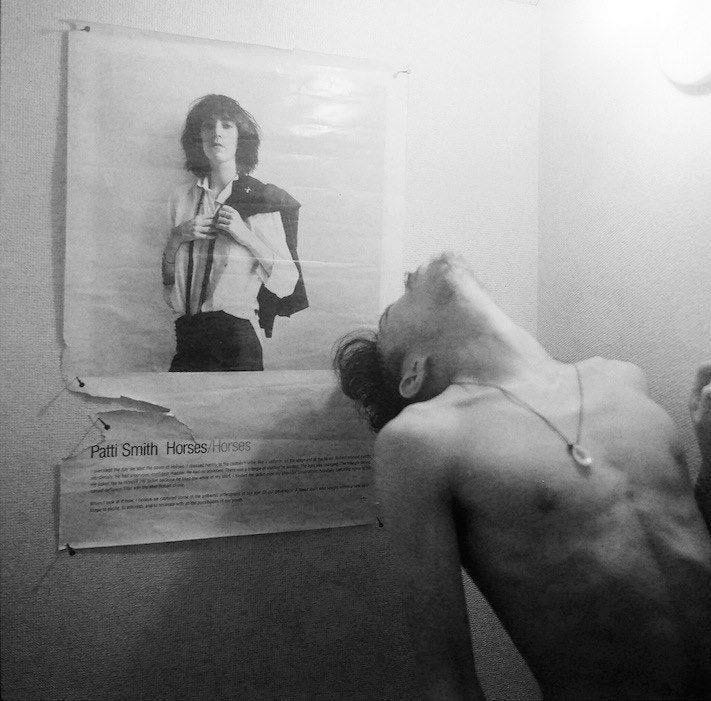

Let’s rewind to 1975 in New York City. The city’s debt is so high, that financial institutions have to step in to bail it out. This is the first vestige of a world to come, a world where politics becomes irrelevant in the face of financial and corporate power. At the same time, the artists in the city are retreating into a philosophy of radical individualism instead of participating in collective action.

They believe that their self-expression and art is radical enough to change people’s minds. This shifts their obligation as artists to merely experiencing the world instead of trying to change it. “The revolution was deferred indefinitely,” one of them says retrospectively in the documentary. “And while we were dozing, the money crept in.”

You see, by detaching themselves and retreating into a sort of ironic coolness, a whole generation was losing touch with the reality of power. Sound familiar? Personally, I think “ironic coolness” is a plague on the youth of today, as well. No one wants to admit they sincerely care about anything at the risk of sounding cringe. Just like in the 70s, this attitude plays into existing systems of power and reinforces their hold over us. Anyway, back to the documentary.

Even as the youth and artists lost touch with the realities of power, the politics of this era came to be dominated by a figure who saw history as nothing but the struggle for it: Henry Kissinger. Nothing reflected this better than his delicate balance of terror nuclear strategy. To Kissinger, the world was an interconnected system in which nations (or other groups) vied for power. And his job was to maintain a delicate balance to prevent everything falling into chaos. This is how he justified his actions in the Middle East pitting Arab countries against each other, to weaken them.

Hafez al-Assad of Syria was the West’s most dangerous opponent in the Middle East at the time. He wanted to united Arab countries against them and saw peace as contingent on the return of Palestinians to their homeland. Assad warned Kissinger that what he’d done would release demons hidden under the Arab world. But to Kissinger, everything could be reduced to nations playing a game of power, even human dignity, survival, and freedom.

Kissinger was serving as Secretary of State at this time under the Reagan administration. For his part, Reagan wanted to double down on America’s role as a moral crusader destined to fight evil in the world. The reality played out very differently, however. Even as Syria’s Assad started utilizing suicide bombing strategies in Lebanon to drive the Americans out, a strategy that would spin out of control and become a hallmark of terrorists in years to come, Reagan still feared the consequences of attacking them directly. Instead, they came up with another easier target.

This was Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, a self-proclaimed revolutionary that was considered mad by other Middle Eastern leaders. Not only did his political isolation make him a perfect target, Gaddafi was starved for international recognition and attention. When the Americans started blaming attacks on him despite having intelligence that pointed at Syria as the perpetrators, Gaddafi owned up to them. Soon, the entire media apparatus, academics, and other cultural actors were feeding into this image of Gaddafi as a global supervillain.

Years later, the same effort would be put into rebranding Gaddafi as a great thinker after he agreed to dismantle Libya’s nonexistent nuclear program. The West would tout this as a great victory in the war against terror and welcome Gaddafi into their ranks only to abandon him again when the Arab Spring came to Libya and he was removed from power. New lies stacked on old lies to create a whole made up world in which Reagan and other Western leaders had defeated their biggest threat in the Middle East.

As we’ll see, these efforts to create a fake reality had taken a page out of someone else’s book. It was in the Soviet Union that the ideas underlying the concept of hypernormalization first started coming together. By this time, it was clear that the U.S.S.R was not going to be delivering on the vision they promised, and their people were starting to lose hope for the future.

Despite the failure of their socialist state, the technocrats began to pretend that everything was going according to plan. Little by little, they became a society where everyone knew that what their leaders said was not real, but they couldn’t imagine any other alternative than playing along with the fake reality that was being crafted. Instead of accepting the new normal, they created something that fit their idealized version of normality. Something hypernormal.

By the 90s, a key architect of hypernormalization, Vladislav Surkov had appeared on the scene advising Vladimir Putin. Surkov saw the people’s lack of belief in politics as an opportunity and didn’t hesitate to turn Russian politics into a theatre where one could no longer tell what was true and what was false. He was what they called a political technologist, and his philosophy that reality was something that could be manipulated as they wished was what kept Putin in power unchallenged for over 15 years.

Surkov sponsored opposing movement with government money: both anti-Nazis and Nazis, for example, and even human rights movements that opposed Putin. The kicker was that he let everyone know that this is what he was doing so no one would know what was real and what was fake. It’s a strategy that keeps the opposition constantly confused. A ceaseless shapeshifting that is unstoppable because it is undefinable. All along, the real power was hidden away behind the stage, exercised without anyone seeing it.

In America, the same tools were adopted as early as the 70s when the U.S army was carrying out military tests on new equipment they wanted to keep hidden from the U.S.S.R. To cover these exercises up, they leaked fake documents detailing the presence of UFOs, fooling not only their enemies but their own people, too. It was a blending of fact and fiction called perception management.

Politicians told dramatic stories that grabbed the public imagination, whether they were true or not, to distract people from having to deal with the complexities of the real world. This fueled the growing belief that governments lied and conspiracies were real. This was partly why people started turning away from politics in the West, because they felt lied to, but it was also because they felt that their actions had no effect.

Despite the mass protests, and the fears and the warnings, the war in the Middle East had happened anyway. No one knew how to change the world. Liberals, radicals, and young people retreated instead to a world they saw as free of frustration and the corruption of politics: cyberspace. To technological utopians, this was a new, safe world where radical dreams could come through.

In reality, they were giant networks of information invisible to ordinary people and the government, created and controlled by corporations. Those who took issue with the idea that there was no hierarchy or controlling powers in cyberspace saw the egalitarian façade of the internet as camouflage for the emergence and solidification of this new financial power that was way beyond politics. After all, these networks were allowing financial corporations to gather an unimaginable amount of information on individuals.

This drove the emergence of a system that had nothing to do with politics. A system whose end was not to try and change things but to manage a post-political world. This explains why after the financial crash of 2008, politicians saved the banks but did almost nothing about the corruption that was revealed. By then, their primary responsibility had shifted. Their job was now to keep the system stable, or inversely, to prevent anything that might destabilize it.

Why? The world seemed so complex and modern technologies so dangerous, that we had entered an age of anxious individuals, frightened of the future. What they wanted was someone to predict outcomes and prepare for potential dangers. Any politician that thought they could take control of society and drive it forward to a better future was seen as dangerous. Politics became just a small part in a system designed to keep the world stable.

One of the reasons cyberspace took off was because people found comfort in seeing themselves reflected back at them, like in a mirror. Corporations created systems to do just that but on a giant scale: AI models, simplified agents, that monitored individuals, collecting large amounts of data about their past behavior and looked for patterns to predict what they would want in the future.

This created a world that centered you as an individual. A safe bubble that protected you from the complexities of the world outside. This idea drew people in, but behind the screen, the program’s simplified agents were watching them, predicting, and guiding their hand on the mouse. With more data being gathered, new forms of guidance emerged. Complex algorithms that looked at what individuals liked and fed them more of the same.

Individuals began to move, without noticing, into bubbles that isolated them from enormous amounts of other information. They only heard and saw what they liked. News feeds increasingly excluded anything that would challenge people’s preexisting beliefs.

Behind the superficial freedoms of the web were giant corporations with opaque systems that controlled what people saw and shaped what they thought. And what was even more mysterious is how they made their decisions about what you should like and what should be hidden from you.

As we know now, these online bubbles have been in large part to blame for the increase in political polarization in the 21st century. Although it started years before, nowhere did we see as clear of an example as in Trump’s 2016 campaign. It was like nothing before seen in politics. Nothing was fixed. What he said and who he attacked and how he attacked them was constantly changing and shifting.

He and his audience knew that much of what he said bore little relation to reality, but they accepted the new reality he was creating without question. Trump’s irreverence toward facts made journalism irrelevant since journalists had, up to now, considered it their job to expose the truth. It’s no surprise that Putin admired Trump.

The oppositions was outraged by Trump, but they expressed their opinions on cyberspace so it had no effect because the algorithms made sure that they only spoke to people who already agreed with them. Instead, their content creation benefited the corporation who ran social media platforms. The radical fury that came like waves over the internet no longer had the power to change the world. Instead, it became fuel that fed the new systems of power and made them ever more powerful.

This is where the documentary ends. Just like in the 70s, it notes, the version of reality our politicians are presenting is no longer believable. The stories they’re telling us about the world stopped making sense. Reality has, again, become something to play with, constantly shifting and changing. We can see this in the news right now. As Israel perpetuates a genocide in Gaza, there’s been a massive exercise in perception management as U.S politicians bend over backward to justify the indefensible actions of the IDF.

And, of course, we’ve seen it for years with the way our leaders and the media have ignored the reality of the climate crisis. These things will come back to bite us if we don’t face them now. Our government and corporate leaders are partially at fault for lulling us into a hypernormalized stupor for all these years, but it’s our propensity to seek comfort and shy away from complex situations that made it so easy for them to do so.

We need to challenge each other to step outside of our comfort zones lest we keep falling deeper into a fake reality in which everything is normal even as our world hurtles closer toward catastrophe every single year. No, this is not normal. And we shouldn’t keep calm and carry on. We should make it loud and clear that we will no longer be playing along with this make pretend world.

We the people need to fight back using the same strategy: manipulate reality by disguising our interests online—let them try to guess our reality.

Powerful message. I think we are just protecting our sanity by avoiding reality.