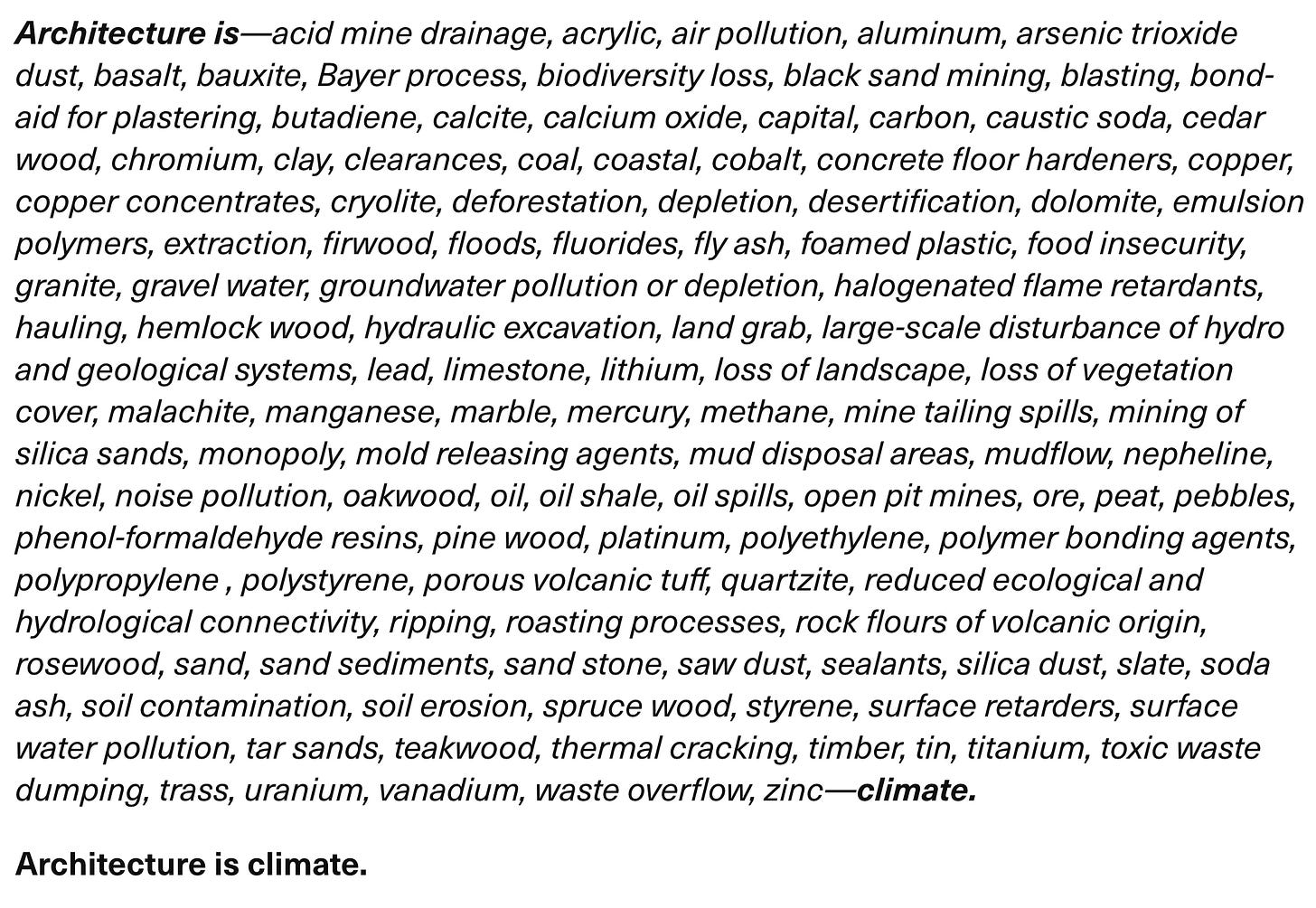

Architecture is climate

What happens when you stop conceptualizing architecture as something separate from the living world? As things that stand in opposition to one another?

False dichotomies abound in societies of men. There’s the philosophical one of good versus evil. There’s historically-entrenched ones like that of capitalism versus communism. And there’s the foundational misunderstanding of man versus nature. That of the built environment versus the natural environment.

Architects, those tasked with creating our built environment, have been reimagining their role in light of the climate crisis. Those well-informed on environmental topics often come across phrases reminding us of humans’ place among the ecosystem, not outside of it.

In this reframing, architecture can no longer be considered as separate from the living world. Instead, architects must acknowledge the interactions between them and take them into account in order to create structures that both endure the changing climate and contribute to adaptation and mitigation efforts.

The truth is that most professions, if not all, will see themselves affected by the climate crisis. Financiers and business executives who fail to limit the environmental degradation their activities cause will later find their portfolios tanked when food and water shortages or extreme weather events disrupt the global supply chain. Many leisure-adjacent economic activities will fall to the wayside when disposable income dwindles and the average person becomes most concerned with survival.

The architects that are taking a climate-informed view of their discipline are making the smart choice of thinking in the long-term. This will ensure that their legacy, the structures they design, persist and become both a safe haven and a beacon of innovation for other to follow in their footsteps.

The creativity and innovation born from this mindset is one of the great joys of sustainability, after all. Today, we will be diving into the fascinating world of green architecture and the ways that trailblazers in the field are changing their methods to meet climate-related goals.

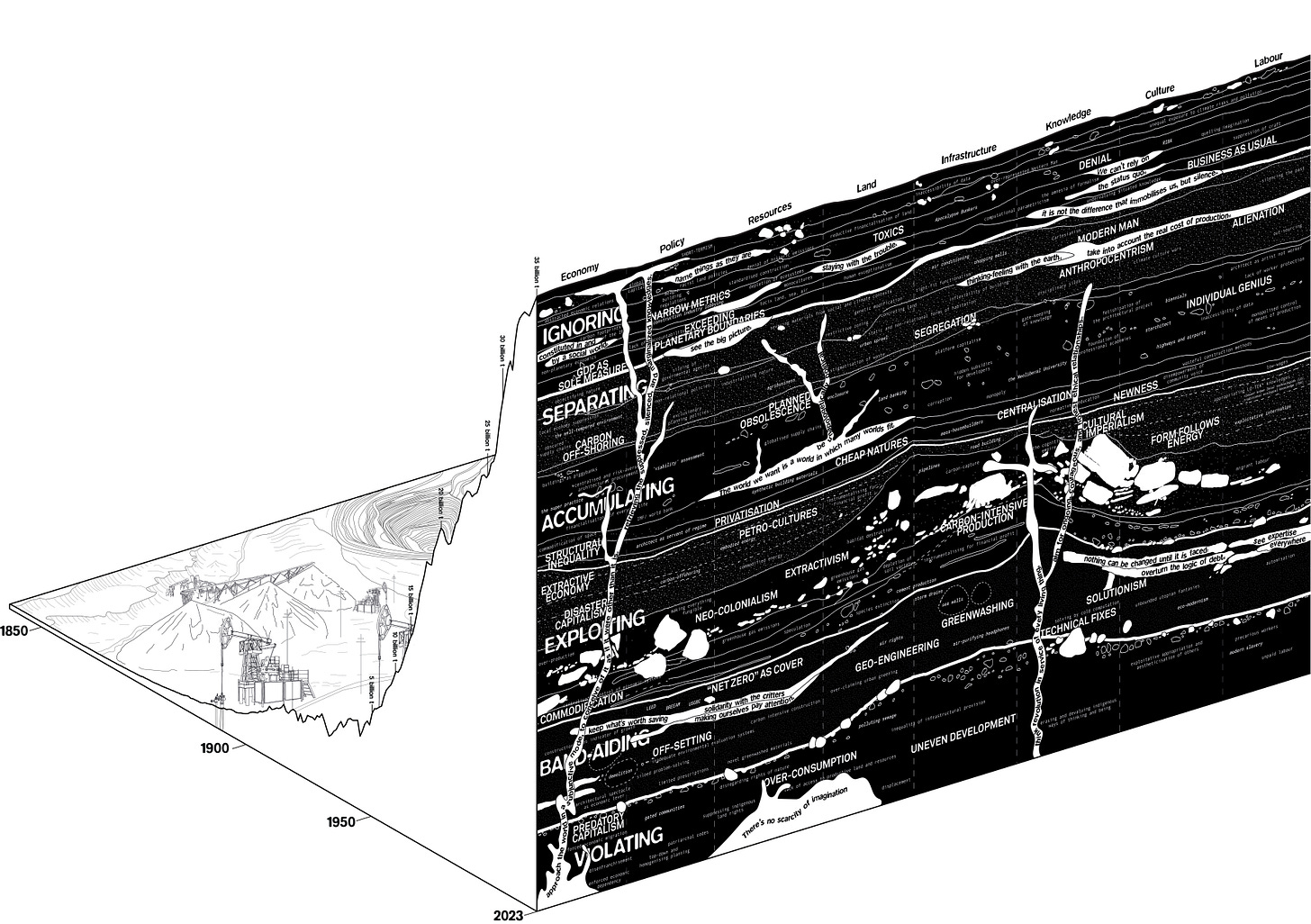

“Architecture has concretized our perilous energy dependency”

This week’s newsletter is inspired by and heavily references a work by the same name that was published in the Chronograms of Architecture. The main highlight of their work was the diagram above. It’s a representation of the rise in concentration of CO2 in our atmosphere and the many interconnected causes that have led to our current crisis. MOULD, the research collective that authored it, writes:

We cannot continue to ask the normative question: “What can architecture do for climate breakdown?” Instead, we must ask: “What does climate breakdown do to architecture?”

They go on to point out was the way that our fossil fuel addiction has come to dictate the form that our built environment will take. The decisions that perpetuate this order are often done on auto-drive (“we’re just doing things as usual”). To change that will require conscientious thinking about each and every step of the process.

Thankfully, there are proven methods of refurbishing existing buildings, even those built for a fossil-fuel-intensive reality, into more sustainable ones. That being said, when you take sustainability into account from day zero and make climate-informed decisions, you can reap the benefits with much less effort. Passivhaus standards are the most highly-regarded framework for this idea.

These standards still prioritize the occupants’ health and comfort, but achieve it with methods that significantly lower the energy requirement. The key is to utilize the surrounding environmental features to passively maintain pleasant temperatures and ventilation. In warm climates, this can look like courtyards and trees outside windows. Windows themselves can be placed strategically facing south for more sunlight and warmth or north for the opposite. In Maine, one ecology center’s architects thought so far as to position the building to block the harsh ocean winds.

Crucial to the success of these passive interventions is a high degree of insulation to ensure that when comfortable temperatures are achieved, they can be maintained with little effort. And once you’ve maximized the energy efficiency of your home, you can take it one step further and connect it to a renewable energy source like rooftop solar. That’s how you reach carbon neutrality or even net positive emissions. Again, even older buildings can be retrofitted to be electrified in this way.

The impact that these methods can have should not be understated. Buildings alone are responsible for 26% of global energy-related emissions. Standards like Passivhaus give property owners and managers a clear path forward to reduce those. There’s no reason that standards and regulations everywhere shouldn’t be demanding this level of sustainability from every new build.

“Careful deconstruction rather than demolition”

Another large source of emissions related to buildings that must be tackled is that of the materials used to build them. Concrete, for example, is the most used man-made material in existence, and cement, which is used to make concrete, is the source of about 8% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Similarly, the steel industry is responsible for 7% of GHG emissions annually.

A significant effort is being made to decarbonize both of these industries, but it’s not happening fast enough. Advocates of more sustainable architecture have zeroed in on two avenues for reducing the emissions related to building materials: choosing renewable resources like bamboo or sustainably grown timber, and increasing the circularity of the materials used.

I wrote about the need for a circular economy in a previous article, but for those unfamiliar, in short, circularity asks that you extend the lifecycle of products and their materials as much as possible before sending them to the landfill. Many will undoubtedly know some of the core principles of this movement, recycling, reusing, and reducing. You can check out my article on the topic to find out just how many more R-words are related to the topic.

Bringing circularity into architecture can mean several different things. For one, it can “prioritize careful deconstruction [of old structures] rather than demolition, to ensure that whatever is removed is either reused or sorted for down or up cycling”. While this process is slower and more laborious right now, architects designing new builds can actually plan for this in the future and purposefully make reversible architecture that is easier to take apart with components that are made to be reused.

Another way to improve the environmental footprint of building materials is to select regionally sourced alternatives since this decreases the amount of transportation-related emissions for the overall project. When you think about it, the globalization that made having Italian marble, Canadian hardwood, and Chinese steel in one house possible is a recent phenomenon.

Take the U.S. In the Southwest, where clay abounds, houses were often made of adobe and stucco. Whereas in the Northeast, the materials available were more often turned into pinewood floor and fieldstone walls. Not only does using local materials help reduce the negative environmental impact of buildings, it has cultural connotations that solidify the regional aesthetic.

Lastly, it’s worth mentioning that the community will reap economic benefits if local materials are chosen over imported ones. The homeowner probably will, too. Some regionally-sourced materials will even be better suited to whatever climate they’re harvested from.

“Transformative, multi-purpose, and evolving”

In a constantly changing world, architecture must also evolve and adapt to different demands. As I mentioned before, to build sustainably one must design taking the long-term impact into consideration. The best way to do so considering that the occupants’ needs could change over time would then be to design multi-use rooms that can adapt to those changes.

When spaces are built to be multi-purpose from the beginning, there is no need to demolish them to accommodate different requirements, effectively playing into the concept of circularity, as well. “The most sustainable building is the one that is already built,” architect Carl Elegante once wrote.

Think about the limitations a traditional office building has and how they mostly sat unoccupied during the COVID-19 pandemic. If those buildings had been designed to be multi-purpose, they could have easily been transformed into residential units. Because of that, this type of design can also serve to reduce urban sprawl and its environmental impacts.

It gives more opportunities for keeping neighborhoods occupied even if a big local player decides to up and leave. Even if the space wasn’t originally designed to be multi-purpose, there are many examples of factories or warehouses being refurbished to meet new needs. Having open floor plans usually facilitates these transitions more than traditionally sectioned rooms.

Rewilding, biomimicry, and more

Architecture and climate are so interconnected that this article could go on forever. If you’re interested in delving further into the topic I certainly recommend you check out the website architectureisclimate.net and read the original “Architecture is climate” article from MOULD on the Chronograms of Architecture site.

Before we wrap up here, though, I’d be remiss not to mention the important role architecture has in fostering a connection between humans and the surrounding living world. Whether it’s through tall windows that look out onto the coastline, creative shapes that blend into the landscape, or even the use of local materials as we discussed earlier, architecture has as much power to make us feel as one with the living world as it does to separate us from it.

The interplay between these two complimentary dimensions is being explored through practices like rewilding, or restoring ecosystems damaged by human intervention. Architects can contribute to rewilding by taking the local biodiversity into account in their landscaping or by choosing to source the materials for building sustainably. These practices also fall under the umbrella of non-extractive or regenerative architecture.

Biomimicry is another interesting intersection between architecture and nature. While it may refer to a structure built only to resemble something from the living world aesthetically, it’s also a source for sustainability innovation. For example, buildings like Council House 2 in Melbourne or Eastgate Center in Zimbabwe both mimic termite hills to achieve natural cooling and ventilation.

There’s no better comparison to drive my initial point in than this one. Just like termites build their hills, complex structures with considerations for ventilation and the like, us humans build our own structures within the living world. There has never really been a separation between our built environment and the natural environment since the prior is a part of the latter.

“Architectures and climates are not separate entities brought together in orchestrated moments. Instead, they are conditions that are produced through one another,” MOULD research collective writes. “No longer standing outside and applying superficial patches to the wounds of climate, architecture is climate binds the discipline and its humans to the scars, violence, and emotions of climate breakdown.”

Architects now have the opportunity to transform our built environment into something that’s in conversation with the living world, but they won’t achieve it by holding on to past heroes and canon. If architecture is climate, MOULD reminds us, when one breaks down, so does the other. It’s time to innovate and reconfigure spaces to improve our connections to the planet and to each other.