Out of sight, out of mind

Invisible networks of labor and production serve the most privileged among us, but they also keep us complacent

Most people don’t think too much about their garbage. Even as billions of tons of trash are produced by humans each year, most destined to end in a landfill if not polluting the living world, many of us don’t give a second thought to what happens once we put something in the bin. This isn’t a moral judgement. The system is designed this way.

We place our waste plants, disposal facilities, and garbage dumps out of sight of our housing developments. We conceal them and sometimes even transform them into less unsightly things. We forget about our waste when it disappears from sight. But our waste says a lot about us, and it never really disappears.

As people in higher income countries (and higher income people in lower income countries) have clustered in urban centers, they have become increasingly isolated from the realities of resource extraction, goods production, and post-consumer waste management. Most would be hard-pressed to name the origin of the apple in their grocery cart or, worse still, the complex supply chain that delivered the shirt on their back to their closet.

This is partly a legacy of colonialism in which the countries in the Global South continue to provide most of the resources and labor required to supply these privileged few. Through these invisible networks, the benefits are reaped in one place while the costs are externalized elsewhere. Refocusing on the subject of waste, this can be seen in “recycled” plastics that end up clogging waterways in Asia or electronic waste that is shipped to Africa and South America.

The fact that these processes are conducted out of sight from the consumer encourages them to stay ignorant and focus on continued consumption instead. This is in direct conflict with the need to conscientize the public as to the environmental and social effects of their lifestyles. It also feeds into the hypernormalization of a reality in which things like the climate crisis feel far away and like someone else’s problem.

Our society’s waste management issues are a poignant topic that showcases our patterns of overconsumption and overexploitation while implicating every single industry. We see it in our food system. Globally, over one third of food produced is never used. In the textile industry, 87% of the materials used to make clothing will end up in either incinerators or landfills.

And since the 1950s, the world has produced more than nine billion metric tons of plastics, but less than 10% of it is ever recycled. By 2040, the production of plastic is expected to rise by 70% compared to 2020 despite the fact that there’s no viable end-of-life processing solution for it.

Incinerating plastic created toxic fumes that endanger the health of all communities in the surrounding areas. Not to mention the many plastics that end up in our oceans and can be expected to stick around for thousands of years. Recent research has shown that plastic pollution doesn’t affect just the animals in these environments, but also the humans that subsist off of these ecosystems.

While the effects of microplastics on human health are still being studied, many chemicals in plastic are endocrine disruptors and, nowadays, we all have microplastics in our systems.

When you are living so entrenched in these systems, waste might seem like too daunting an issue to even do anything about as an individual. However, there’s certainly solutions being proposed and products being engineered to divert materials from the landfill at their end-of-life. Let me introduce you to the concept of a circular economy.

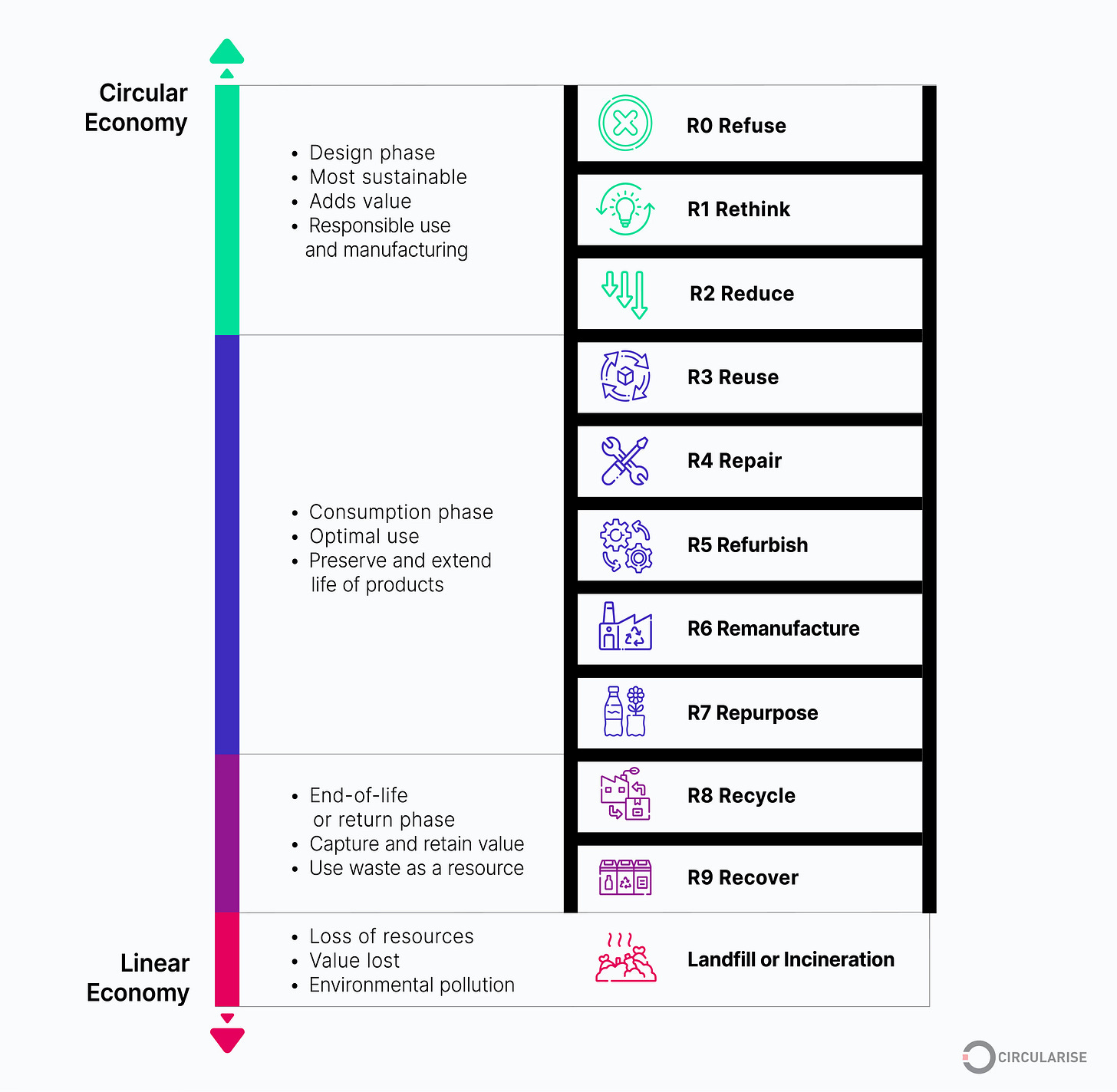

This stands in juxtaposition to our current linear economy in which goods follow a straight arrow from producer to consumer to landfill. In a circular economy, what would usually be thought of as waste is re-valorized in one of many ways and reinserted into the consumption cycle for continued use. There aren’t just three R’s (reduce, reuse, recycle), but twelve.

The principles of circularity must be taken into account from the conception and design of a product to ensure that it is repairable and it avoids any unnecessary implements like excessive packaging. Repair and refurbishing is, in fact, a huge part of the circular economy which is why those familiar with the concepts feel such animosity toward companies like Apple that purposefully limit the repair options of their customers and engineer planned obsolescence into their products.

Planned obsolescence refers to a product that is designed and expected to function until a predetermined expiration date. When it comes to iPhones, people speculate that Apple does this in order to encourage the purchase of newer models. However, the issue extends way past consumer goods. The very concrete structures that make up our countries’ infrastructure is aging and deteriorate significantly after the 50 year mark.

This is an emblematic case of a world constructed without long-term sustainability in mind. If the principles of circularity had been taken into account when designing our infrastructure, our ability to repair it far into the future would have been top of mind. That’s why I insist that sustainability must become a value as pervasive as honesty, something we do because it’s simply the right way to do it.

I know there’s many out there that would bristle at the onus being put on them to adopt sustainable habits. After all, major corporations and the richest 1% are responsible for a disproportionate amount of emissions and waste production. But corporations, and every organization really, is made up of individuals. By learning to incorporate the principles of circularity into your personal life, they will pervade every other aspect of your life, carrying over into your decision-making criteria at work.

The first step to reducing waste is always at the point of purchase. Ask yourself if you really need this item. If not, why buy it? Some would do it for the brief dopamine hit it provides, but I would encourage you to look for experiences that can brighten up your day in a similar way. Spend that money on a nice massage instead or an outing to somewhere you’ve never been.

If the purchase is necessary, always look for producers local to your area. Better yet if they follow any sustainability principles— look for words like organic, regenerative, and recycled. Learn to avoid plastic, especially single-use plastic, whenever possible. In fact, anything single-use is to be avoided except in medical or industrial settings, in which they serve a specific purpose.

When looking at alternatives, it’s usually best to choose those made of reusable materials like glass or metal. For example, metal straws or cutlery to take to work for lunch instead of plastic disposable ones. Of course, this only contributes to diverting waste from the landfill if you successfully form the habit of using them.

In the case that you absolutely need something disposable, look for biodegradable options. These will usually be natural materials like paper, cardboard or bamboo. Be careful, though, since many paper cups and plates have a plastic lining and, if they do, they actually cannot be recycled.

You can find tons of easy hacks and tips on the internet if you search for zero-waste bloggers or social media accounts. The key is not trying to do everything at once, but taking it one step at a time. You might overwhelm yourself otherwise. But if you choose to, for example, start phasing out single-use plastics from your life, I recommend focusing on that until you get the hang of it before adding anything else to your plate.

The goal is to adopt these habits for good, so take your time and make sure you’re doing it in a way that’s sustainable for you. There’s no shame in starting with whatever seems easiest and most accessible. You’ll see that once you start seeing the world through this lens, it will become much easier to identify the options with the least packaging and replace plastic with better materials.

As I said before, sustainability is a value just like kindness. It takes practice, but it certainly gets easier with time. Our individual consumption habits may not make a huge dent in global emissions, but by choosing the reusable option instead of the disposable one, you will be sending a message to the producer that there are people out there who want better alternatives.

Most of all, make an effort to locate yourself in the complex, global system we’re living in. Pay attention to where your goods come from and try to learn more about what happens to them once you’ve put them out on the curb. Not everyone needs to be an expert, but living in blissful ignorance is a surefire way to avoid thinking of the environmental and social implications of our actions. All it takes is one step: open your eyes.