The medium is the message

The form our media takes affects how we process the content delivered. What does that mean for effective climate communication?

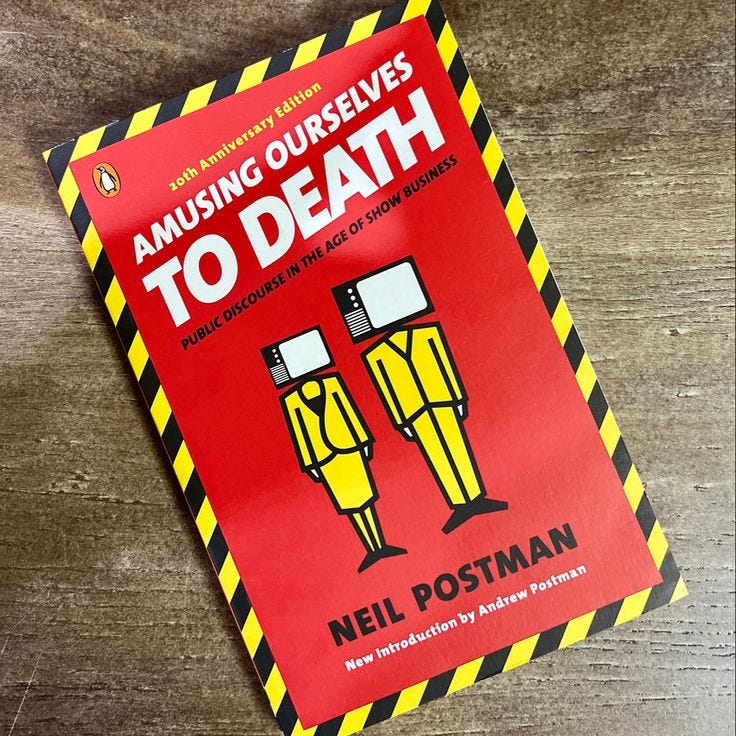

Ever since reading Neil Postman’s book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, I can hardly help but reference it when conversations turn to the effects of modern media on our society. One example that comes up often is that of emotional burnout. I’ve talked with friends more than once about the exhaustion that hits you when you try to keep up with worldwide news coverage.

We’re constantly bombarded with tragic and upsetting stories from all corners of the world. In business school, a professor once told our class that we needed to subscribe to the most reputable news outlets and stay updated on the daily. Anyone with a shred of empathy who has done this has no doubt ended up overwhelmed and hopelessly pessimistic.

Postman argues that we were never meant to be privy to everything happening all at once. In fact, when we concern ourselves with stories that are, in fact, irrelevant to our daily existence and that we have no way of changing, it simply makes us feel powerless and distracts from the things over which we do have influence in our immediate surroundings.

A good example of this is a country’s presidential election or equivalent. Whereas most of the population is paying attention to who is elected as the leader of their country, in reality, the president’s policies will usually have subtle effects over the long-term. On the other hand, local politics at the city-level tend to affect residents more obviously and directly. However, few people are aware when their city officials are being elected, most likely because the media they consume is tailored to a global audience and not local ones.

Postman makes an interesting point about the introduction of images in our news media decades back, as well. People who lived in remote areas of a country would have prior considered news from the capital to be only tangentially relevant since it covered people they didn’t know in places they’d never been. But once the technology to print images and disseminate them widely came into existence, something remarkable happened.

With only adding an image, the audience that previously disregarded the importance of the news attached felt like they understood and knew these people they’d never seen in places they’d never been to. Postman writes this as an example:

You may get a better sense of what I mean here if you imagine a stranger's informing you that the illyx is a subspecies of vermiform plant with articulated leaves that flowers biannually on the island of Aldononjes. And if you wonder aloud, "Yes, but what has that to do with anything?" imagine that your informant replies, "But here is a photograph I want you to see," and hands you a picture labeled Illyx on Aldononjes. "Ah, yes," you might murmur, "now I see." It is true enough that the photograph provides a context for the sentence you have been given, and that the sentence provides a context of sorts for the photograph, and you may even believe for a day or so that you have learned something. But if the event is entirely self- contained, devoid of any relationship to your past knowledge or future plans, if that is the beginning and end of your encounter with the stranger, then the appearance of context provided by the conjunction of sentence and image is illusory, and so is the impression of meaning attached to it.

At this point in the book, Postman has only just explained the effects arising from the invention of the daguerrotype and proliferation of the telegraph. However, his analysis is startlingly applicable to our current society.

This would be a good time to let you know that this book was originally published in 1985 and focused on the shift from print to television. Reading it 40 years later, though, feels like reading the work of a prophet. How can a book from decades before social media was invented predict some of its societal effects so accurately?

His description of a peek-a-boo world “where now this event, now that, pops into view for a moment, then vanishes again” describes our social media feeds far better than its actual subject, television. It’s a world that has “no coherence or sense”, asks nothing of us, indeed “does not permit us to do anything” (except like, share, and comment), and is “endlessly entertaining”. Postman talks about how we brought TV (and the peek-a-boo world) into our homes, but today, our smartphones are practically glued to our hands.

If you were to replace all mentions of television in this book with smartphones, it would still largely make sense to a modern audience. Take this next point, for example. In the 80s, Postman says, television had achieved the status of myth as understood by Roland Barthes. That is to say, “a way of understanding the world that is not problematic, that we are not fully conscious of, that seems, in a word, natural. A myth is a way of thinking so deeply embedded in our consciousness that it is invisible.”

I see this reflected in the way we’ve come to rely on our phones, or the internet for that matter, for everything. Despite our increasing over-dependence on these technologies, most won’t stop to think about the potential risks that opens our societies up to. One particularly striking example to me is the idea that one day, a solar flare or other unpredictable event might cause widespread blackouts and sever us from the worldwide web.

I’m not saying it’s likely to happen, but it’s possible, and most of us would be woefully unprepared to navigate such a world for more than a few hours. Another scary idea is the possibility of losing access to troves of information that only exists on the internet. If they’re not stored in hard drives and only on the cloud, and if there’s no hard copies in existence, this is content that could easily be lost forever.

Anyway, I could share quotes and examples from Amusing Ourselves to Death forever. But this is a publication about sustainability communication and climate and culture. So, why are we learning about this today? Well, as the book explains, each form of media has different features. Some, like the written word, are useful for expounding on logical arguments. Others, like television and social media, demand spectacle.

As every subject of public interest (politics, news, education, religion, science, sports) found it’s way onto television and now social media, the discourse around it inevitably takes the form of entertainment. In order to communicate effectively on a subject like climate, which is not purely entertainment and does ask something of the audience, we must navigate these biases and try to make them work in our favor.

How do you make a lasting impact on an audience that is trained not to hold any thought or feeling as they swipe on to the next image or video? How do you impress on them the severity of an extinction-level risk when they’re used to seeing catastrophic news several times a day and carry on with their lives without a second thought? How do you get their attention with severely alarming statistics and facts when everyone from politicians to doctors are now putting on a show to get their attention every minute of every day?

These are the questions we must reckon with. As important as some climate messaging is, facts and figures don’t really do numbers on Instagram or TikTok. And I know what some are going to say, why would you rely on media platforms designed for entertainment to disseminate serious messages? It’s simple. We need to meet our audience where they’re at. Unfortunately, that’s not Substack for most.

I’ve written about my project to create pop sustainability content in a previous post. This is meant to use the language of entertainment to convey serious messages while competing with other content creators. By adopting the visuals and wording of creators that are already successful, you capitalize on the fact that people tend to trust those they like more than those they don’t.

This is a delicate balance. Unfortunately, straight-forward science communication is not working to move the needle on the public’s perception of the climate crisis. Even as more people come to accept the reality of the situation, few actually adopt more sustainable habits and fewer still vote with the future of our planet in mind.

The need then arises to infiltrate the public consciousness in different ways. The first challenge being to catch people’s attention in a media landscape where every single company and creator are vying for the same real estate (or the so-called attention economy). This is the perfect example of why every topic, no matter how serious, has to package itself as entertainment on television or social media platforms. If you want engagement, you need to be engaging.

Apparently, it’s been a while since facts really mattered in the public discourse. Postman includes an excerpt from an article from the New York Times about Reagan. “Reagan Misstatements Getting Less Attention” it reads.

President Reagan's aides used to become visibly alarmed at suggestions that he had given mangled and perhaps misleading accounts of his policies or of current events in general. That doesn't seem to happen much anymore.

Sound familiar? I’ve written about this phenomenon and its normalization in a previous article on hypernomalization. As we’ve come to accept that our leaders and institutions are giving us a modified version of reality, facts and figures have come to matter less and less. Instead of relying on numbers then, we must learn to communicate with stories.

This addresses the issue of making a lasting mark on people’s memories when we’re conditioned to forget the last thing on our feed as soon as we scroll to the next one. Sustainability communication must rely on storytellers that can weave themes into the subtext of their work. The trick is to do come up with unexpected narratives and to avoid being didactic.

Now, I know that some people who care about mitigating the climate crisis will take offense to this less serious form of communication just like some psychologists protest the proliferation of pop psychology. I won’t deny that it has its disadvantages, namely the watering down of information for mass consumption. However, we can’t pick and choose our methods in the face of an extinction-level crisis.

Different communication styles will appeal to different audiences. Thus, a multi-pronged approach is needed. We need both the official science communication and the pop sustainability content to reach further and wider. We must prove to people that you don’t have to be any one way to be more mindful of our impacts on the planet. If that requires some of us to put on a show, so be it.